Reports of export bans and ‘saving art for the nation’ often appear in the press. Many significant works have been prevented from going abroad in recent years, such as a Van Dyck self-portrait and a ring which belonged to Jane Austen.

But alongside these success stories, calls for export licence system reform persist. Many believe it is outdated, ambiguous and not robust enough.

Currently, when an important art work is sold, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) is alerted before it is exported, and any export application will be examined in detail.

The DCMS may decide to submit the application to the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art, which advises ministers whether a cultural object is of national importance under the ‘Waverley Criteria’ (see below).

A hearing takes place, usually attended by expert advisers, legal and other professionals. The object is displayed and written submissions will have been made beforehand.

The issues at stake are not straightforward. An object considered of ‘outstanding aesthetic importance’ by one expert may be viewed differently by another. These hearings can become animated.

This was my experience when I attended a tribunal to make submissions for a potential exporter.

The hearing was held at the National Gallery, the Old Master at issue on display. Our advice was that, while it was a “beautiful painting”, it was not “of outstanding aesthetic importance” (Waverley 2) and didn’t meet the other Waverley criteria.

Before I had finished speaking an eminent independent assessor, no longer with us, could not contain himself, proclaiming aghast: “Well then, let’s have a wholesale export of England’s heritage!” I moved diplomatically on.

Even if the work satisfies one of the Waverley Criteria and is considered worth ‘saving,’ that is not the end of the story. Funds need to be raised and the purchaser has to comply.

A recent case concerning the V&A and its attempt to purchase the Clive of India flask is an example of the current export licence laws failing to provide a straightforward solution.

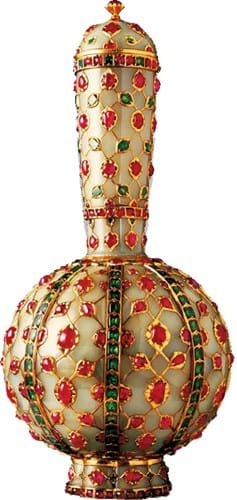

The Clive of India flask is a jewel-encrusted jade flask made for the Mughal royal court in the first half of the 17th century. It was acquired by Lord Clive of India in the 18th century and passed down his family until 2004, when it was sold at Christie’s to Qatar Museums.

In 2005 Qatar Museums applied to the UK government for an export licence. This application was deferred, giving the V&A time to raise funds to purchase the flask. After fundraising had begun, Qatar Museums withdrew its application and the flask stayed in the UK.

Earlier this year Qatar Museums submitted a further application to export, which was again deferred. The V&A began fundraising, but the export application was withdrawn once more.

Qatar Museums’ motivations are not clear. It seems unlikely that the work will ever be granted an export licence, as it has been deferred twice now. A loan agreement with the V&A is apparently under discussion, arguably an unsatisfactory long-term solution for either party.

But what is the solution? If more robust rules are introduced, then surely they must be nuanced enough to balance the individual’s right to own property with the preservation of cultural heritage.

The Clive of India flask was apparently looted from the Mughal Emperor, Mohammed Shah, by the Persian monarch in 1739.

Perhaps the Mughal Emperor’s descendants may also make a claim – a scenario not unknown these days. The Elgin marbles were removed from Greece to Britain in the early 1800s, and this dispute is still ongoing.

The Waverley Criteria

The Waverley Criteria are named after the chairman of a 1950 committee appointed to consider and advise on export policy in relation to cultural objects. They are as follows:

Waverley One: Is the work so closely connected with our history and national life that its departure would be a misfortune?

Waverley Two: Is it of outstanding aesthetic importance?

Waverley Three: Is it of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of art, learning or history?

The cultural object only has to satisfy one of the criteria to qualify.