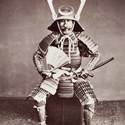

As the title of Daniella Dangoor’s exhibition coming up at the London Photograph Fair Special Edition on May 19-20 puts it, he is the Last of the Samurai.

The now retired dealer is selling her personal collection of around 40 photos – typically albumen prints taken from wet collodion negatives – on this theme. The view of this young samurai, taken by Japanese photographer Suzuki Shin’ichi I in Yokohama in the mid 1870s, was the second she bought.

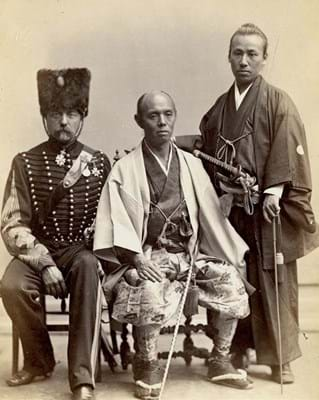

All the images were taken in the 1860s-70s when Japan was emerging from its years of isolation. Dangoor says: “Although the photos are beautiful in themselves, they show a point in time and send a story, because there are 20 years in which everything changes in Japan.”

Modernisations

The country had not been completely closed off when the US Admiral Matthew Perry arrived in 1853 – the Dutch had been trading near Nagasaki and some technical advances had filtered through – “but suddenly everything changes and a huge modernisation begins”, adds Dangoor.

The societal and political developments dominated by the 1868 Meiji Restoration left no place for the once dominant samurai warrior caste. An army formed in the early 1870s meant compulsory military service for males of all classes with weapons no longer the prerogative of the samurai. Five years later their caste was abolished.

The introduction in 1873 of compulsory military service for all males, regardless of class, made the samurai an anachronism.

Starting off

Dangoor says: “When I bought the first few I wasn’t buying them because they were samurai but because they interested me as photographs. Only later I started to see a pattern in what I was buying.”

She started as a collector when working in television and was interested in Japanese art and design.

“I happened upon Terry Bennett, one of the first dealers in Japanese photography, at the first Photo Fair. He was there with his Felice Beatos and I bought one, which started me off, not just on samurai but also Japanese occupations etc,” she says.

She was a dealer for about 30 years, selling at Portobello Market, Cecil Court and Museum Street in London before working with a friend who had a gallery in Paris.

This Last of the Samurai collection is offered as a whole with the price – on application – understood to be a five-figure sum.

Mix of photographers

The collection features a mix of European and Japanese photographers, such as Nadar, Shimooka, Suzuki and Disdéri, taken 1860-77. Most photographs purporting to be of samurai, and often used as illustrations in books and magazines, were taken well after 1877, after the samurai system was abolished, in commercial studios, with actors or studio assistants dressing up in samurai clothes and armour, for the benefit of the tourist trade.

This collection, showing the last of the warrior caste, has been researched and catalogued by Sebastian Dobson, a leading authority on early photographs of Japan. Several prints constitute the only known copies, with most of the rest known in only a few copies, held in museums and private collections.

Despite their anachronistic nature within society by the mid 19th century, Samurai scholars actually played an important part in in diffusing photography across Japan.

A community of scholars of so-called Western Studies based in Nagasaki learned about photography as part of the regular transfer of information that took place through the local Dutch trading settlement at Deshima (the artificial island constructed for the exclusive use of a small group of Dutch East India Employees in Nagasaki in 1636).

Certainly by 1841, information about photography was circulating among educated members of the Japanese ruling class, including Samurai.

One important centre of photography was Kagoshima, the capital of the Satsuma domain, whose lord Shimazu Nariakira devoted considerable effort and funds to scientific research, partly in an effort to modernise his clan’s army. He appointed samurai scholars to investigate photography and secretly ordered a camera from the Dutch in Nagasaki in 1843.

The daguerreotype apparatus did not arrive until 1848 and the Satsuma scholars spent the next few years trying to make the leap from book-learning to actual photographic practice.

A surviving group of rough, undated paper negatives suggests that some progress was made c.1854, but the first daguerreotype was not successfully taken until 1857. The resulting image, a blurred portrait of Shimazu himself is now designated an Important Cultural Property and is celebrated as the first photograph of a Japanese taken by a Japanese.

Original works

The London Photograph Fair Special Edition will be held in the Great Hall of King’s College London. Organisers say: “On view and for sale are unique and original works from the entire history of photography from the 1840s through the 20th century. Vintage modernists rub shoulders with rare daguerreotypes and original 1960s film and fashion press prints.”

The event coincides with Photo London which takes place next door at Somerset House.