A taste of the colourful accounts and varied material these works gave their medieval audience is available in a group of 36 vernacular manuscripts in the exhibition Talking at the court, on the street, in the bedroom: Vernacular manuscripts of the Middle Ages. The show, which runs from February 23-March 16, takes place in the New York branch of medieval manuscript and jewellery specialist Les Enluminures.

The manuscripts included cover subjects from history and religion to medicine. They were produced for the use of people at many different levels of society – aristocrats and clergy as well as townspeople and private women.

Masses not educated classes

Crucially, they were written in everyday languages such as French, German and Italian rather than the Latin reserved for the educated classes and Church.

“These texts bring us closer to the people who wrote and used these languages every day,” gallery founder Sandra Hindman says, and compares delving into them to “the experience of reading a good book today”.

The show has been a long time in the making. Hindman, who has branches of her business in Paris and Chicago as well as New York, likes big projects and the accumulation of stock usually takes place well before the development of an idea for an exhibition. However, a continued interest in vernacular texts adds to her confidence that the show will be a success.

“We have been noticing that these texts have been really sought-after in the past five or 10 years,” Hindman says. “In part this is simply because they are more readable – if you can master the scripts – and the subjects are more accessible.”

Universities are particularly keen buyers, she adds. With their lively subjects and more familiar languages, these texts are more likely to appeal to students of history.

Rules of conduct

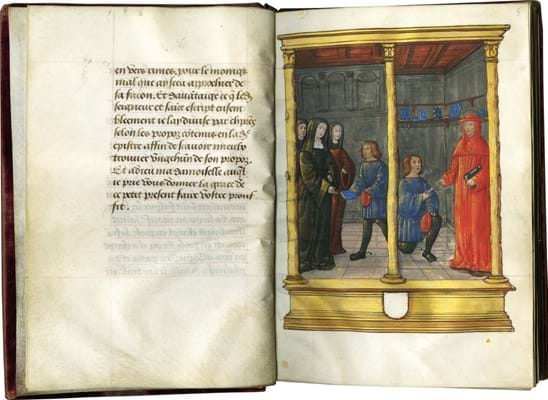

Among the works is a translation into French of St Jermone’s letter to the widow Furia. The epistolary work provides advice on the preservation of her widowhood, laying down rules of conduct for her guidance in the dangerous world of ancient Rome. The volume was owned by Anne de Polignac, a twice-widowed French aristocrat who is pictured in the text. Most of the 36 manuscripts in her library were in the vernacular.

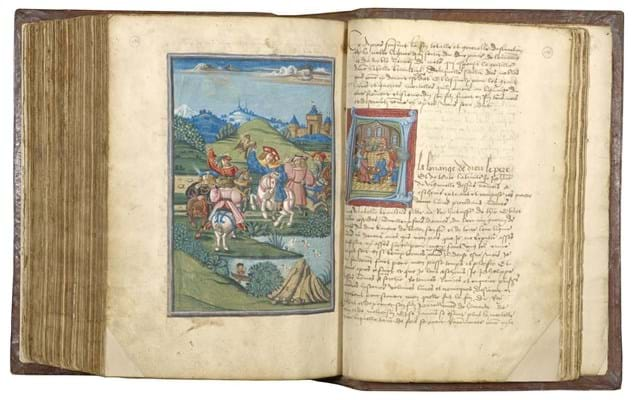

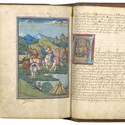

There is also a 15th century Italian translation of the famous Roman history by Valerius Maximus De fatti e detti… or Deeds and Sayings.

The text is a collection of historical anecdotes relating how the earliest Romans lived and the translation has been attributed to Italian humanist Giovanni Boccaccio, author of the Decameron.

Though the attribution is not certain, this is the first copy out of 32 manuscripts persevering the text to appear on the market in at least a century and offers the chance to reopen the debate.

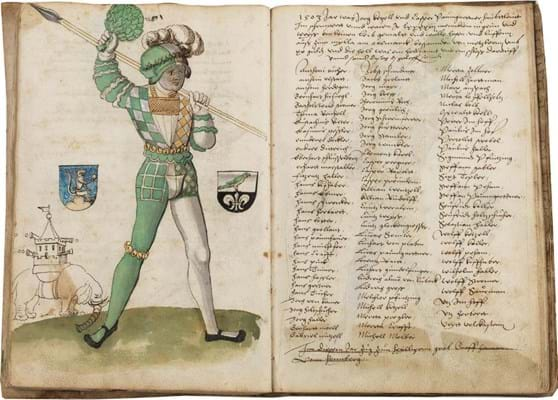

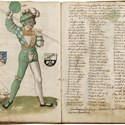

Then there is the German Schembart Carnival Book (1550-1600), which is a complete witness to the famous Schembartlauf carnival parade held in Nuremberg from 1449-1539.

It includes more than 60 full-page illustrations of carnival costumes from each year the carnival was held together with 22 drawings of floats that accompanied the pageants from 1479.

Laura Light, director and senior specialist at Les Enluminures also worked to organise the show and is the author for the catalogue Shared Language: Vernacular Manuscripts in the Middle Ages, published to accompany the exhibition.