Many readers of ATG are collectors and these pages are testament to the scope and variety of our endeavours.

A gentle transition into dealing in some way or other is a logical step and not uncommon. Far fewer make the leap to researching and publishing their passion. This is a great shame as in many cases the expert knowledge accumulated over the years is unique, invaluable and inspiring.

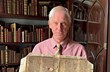

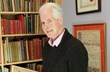

For decades Mavis Eggle was a well-loved member of the Provincial Book Fairs Association. She travelled the country with her husband John selling at book fairs and building up her outstanding collection. Now in her eighties, she has stopped dealing and turned her attention to documenting this collection in Books as they were bought.

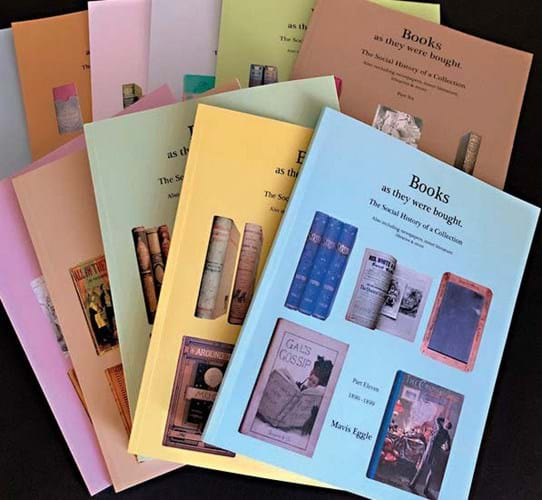

This impressive 16-part work takes a decade-by-decade look at the social history of printed works.

What makes her books so remarkable is the way they recreate the past in such a modern and predominately visual way.

Bright, readable and full of fascinating insights, they are now on sale in a London bookshop and on the internet.

Part Eleven, the 1890s, has just been issued and here we find out more about the series and its author.

The 'Books as they were bought' series written by Mavis Eggle – planned in 16 separate parts, each one covering a decade of publishing progress from the 1790s to 1950. Part 11 is on top.

How did you begin collecting books?

Mavis Eggle: It was a jumble sale at my children’s school. I found an 1890s book and I was amazed that something as old as that had lasted that long.

I brought it home and turned the radio on to hear the terrible news about Aberfan, so I can date that to October 1966. I don’t still have the book, I wish I did. It was a copy of Ovid’s poems.

Before that we lived on a farm in Wiltshire and as a little girl I was always collecting something – fossils, shells, bones and what have you – and I do still have some of those.

How would you describe your book collection now?

Well, it isn’t just books any more – there’s an old school slate in the latest part. I began to collect printed material from any time as long as it was authentic. The main criterion was that it had to look exactly as it did when it was made, so condition was very important too.

In the end I had a representative sample of books, newspapers, magazines and ephemera from the late 18th century up to the 1940s.

So Books as they were bought is me recreating the market, the historical background, to show people the shop window as it existed in the past.

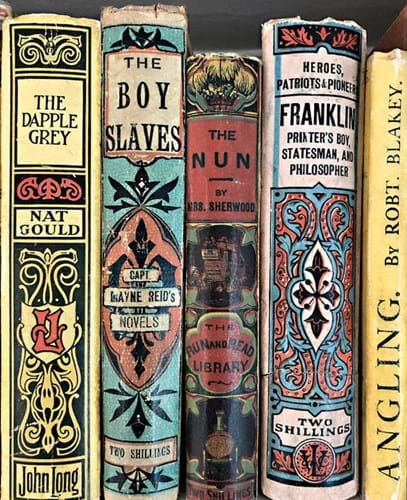

Books for the commuter – the red one in the middle is from the ‘Run and Read Library’ and, in case the target audience were in any doubt, it has a train and a stagecoach on the spine.

So it isn’t the text of the books you’re interested in?

Not usually. I’m not a literary type. And it’s much easier, and cheaper, to build up a collection if you’re more interested in the thing itself rather than the content.

I don’t mind odd volumes and I’m rarely looking for what everyone else is looking for.

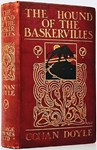

For example, I needed a Strand Magazine for the 1890s and got one for a few pounds. If I’d wanted a copy featuring Sherlock Holmes it would have been a few hundred pounds.

It’s the parts of the historical jigsaw, the way of life and the social change that interests me.

What made you focus on that?

I was bookselling as a hobby at the weekly St Albans market. At the first one I took £6 and the rent was £4, which I thought was a huge success.

Then that closed down so I ran a monthly book sale here in Harpenden from 1979 for about 20 years.

I didn’t make any money but I did see a lot of material coming through.

One day I bought someone’s auntie’s collection of romantic fiction in wonderful 1930s dustjackets and I just didn’t want to get rid of them. It was like going back in a time machine to a forgotten world.

I still have some of them. I showed them to a lovely lady, Mary Hutchinson, who belonged to the PBFA and she said “you ought to be a proper dealer; join the PBFA” and I thought, “I couldn’t do that!”

But I did join late in 1979 and at their book fairs realised just how much other stuff was surviving – newspapers, magazines, everything really – right back to the 1700s.

You could easily buy the things I’d only ever read about. And I was hooked.

Are fairs the best place to buy?

They certainly were for me as there were not many good bookshops within reach.

Dealers’ catalogues were a great help – I especially remember the first yellowback catalogue from Jarndyce in 1990 – but fairs were always exciting. You never knew what you’d find, and that’s still true today, fortunately.

People tend to put their most unusual and best stuff away until a big fair and you can also make good contacts. I liked going around when it was quiet.

Other dealers were very helpful when they knew what I wanted; which is another reason to join an organisation and take part. It must be the same for antiques.

Was there a lightbulb moment when you decided to write about the collection?

Not to start with, but it began to grow on me that I ought to do something. I knew I’d got a good representative sample of a lot of material and I knew other people might like to see it.

Ruari MacLean’s books on Victorian bindings were a big inspiration and I had bought all the other reference books I could find.

At home we’d acquired a computer but I didn’t really use it. I didn’t type. And I didn’t take photographs, never mind linking them to the computer. It was very frustrating.

Then one day in 2003 our 16-year-old grandson came over, understood it straight away and started me off. Since then I’ve had advice from a variety of people and I think I now know what I’m doing!

So, thanks to him you have put together 11 superb books about the social history of printing

Yes. I’ve learnt more history as I write them than I ever learnt at school. It’s all linked.

Cloth-covered books came along in the 1820s and this made them more affordable, so more people could read them. Free public libraries started in the 1850s but only in big towns. Also in the 1850s WH Smith negotiated an exclusive contract to operate railway bookstalls. People needed smaller, lighter books to read on trains during their commute, so paper-covered books, yellowbacks, came along in bright colours.

Then from the 1860 photography began to appear in books and in the 1890s in newspapers.

By the 1860s, photographs like this one appeared in books although they had to be ‘tipped in’ by hand.

Colour printing began to take over from hand colouring in the 1860s and by the 1880s was cheap and reliable, so what happened to all the hand colourists? I’m really writing about the social history as much as the books.

Newspapers are the best sort of social history: they tell you every tiny detail of what’s going on at the time and of course you get adverts too. Newspapers were astonishingly prevalent in the late 19th century. One thing that tends to be forgotten is that in the early 19th century many people were jailed for selling newspapers that were cheap enough for working men to read. The government was scared by the revolution in France.

How does each part take shape?

The biggest problem is deciding what to leave out. Each part is 94 pages and they fit into slipcases so there’s no leeway – I can’t show some treasured items. I weed stuff out; very occasionally I have to borrow an image of something I feel I have to include but have never tracked down, most recently a copy of the socialist Clarion newspaper.

Then I take the photographs and set it all out on the computer. I do it all myself. When it’s ready I send the memory stick to the printer and after the proofs are checked they are printed, put into covers and delivered to the book sellers who bring them before the public.

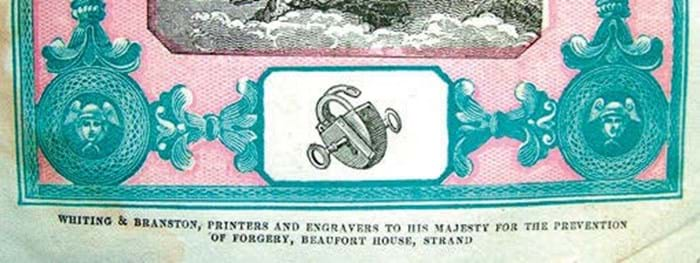

This 1824 title page is by 'Whiting & Branston, Printers and Engravers to His Majesty for the Prevention of Forgery'. It seems to be the first appearance of the elaborate patterns still used today to make life difficult for counterfeiters.

What is the next stage?

I’ve nearly finished part 12, which is the first decade of the 20th century. They are gradually coming to the attention of university libraries, research institutes and special collections here and abroad.

I want them to be used because nobody is ever going to be able to recreate the collection. These days you just don’t see the material: it’s gone now, some is just too expensive, but even if you were a millionaire you couldn’t find examples of everything.

So I’m driven by the idea that I owe it to future enthusiasts to document it all, right up to the 1940s, which will be part 16 and the last one.

And the future of the collection itself?

Eventually I would like it to be available for research because there’s so much more to it than I could write about. But where, I don’t know. If I could find an institution to have it all that would be super but I do want it to be used and to be seen. I just hope that might be possible.

Jeremy Carson adds: Hopefully that will happen in time, but in the meantime we can all enjoy her collection via the pages of her books. They are available at £20 each from Second Shelf, 14 Smiths Court, London, W1D 7DW (020 3490 2800) and online from bibliography specialist Scott Brinded (stpaulsbib@gmail.com)

A member of the PBFA, Jeremy Carson has collected, written about and dealt in old books for over 25 years.