A plaque by the front door of Freeman’s six-floor 1808 Chestnut Street premises proclaims the firm’s roots. It’s a proud boast here that the firm was started by Tristram Bampfylde Freeman – a failed Covent Garden printer turned respected Philadelphia auctioneer – in 1805.

In a city of historic milestones, this is America’s oldest continually running auction house. Sotheby’s, which opened an office in New York in 1955 and Christie’s, a 1977 entrant to the US market, are relative New World newcomers.

And in a country that celebrates its past like no other, it could have been tempting for Freeman’s to rest on such historic laurels.

But there is little sentimentality in the art market. Twenty years ago, as the firm approached its bicentenary, it was a shadow of its former self. Choice consignments were leaving the city for New York. Business was lost to local rivals. Close to 50,000 lots a year were rolling through the Chestnut Street storerooms but at an average of under $100 apiece. Change was required.

The years 1998-2000 were pivotal. With serendipitous timing, Phillips’ North American president, Paul Roberts, was scouting US regional auction houses and thought Freeman’s fitted the bill. On Roberts’ departure from Phillips in 1998 to become deputy chairman of Lyon & Turnbull in Edinburgh, Samuel ‘Beau’ Freeman II, the sixth generation of the clan to run the firm, saw the opportunity to progress the family-run business via auctioneer professionals with outside experience.

Roberts was invited to take on the role of president of Freeman’s. His key early recommendations: that Freeman’s rehire former director Hanna Dougher and bring on board Edinburgh-native and paintings specialist Alasdair Nichol from Phillips New York.

“For the renaissance of Freeman’s to be successful, we needed Hanna’s organisational skills and the art market genius of Alasdair,” Roberts recalls. At this point Nichol was already becoming a household name thanks to his appearances as a valuer on the PBS version of Antiques Roadshow.

With Dougher as chief operating officer and Nichol in the role of vice-president and head of fine art, the trio began rewriting the auction house’s strategy, rationalising its weekly general sales and improving the firm’s infrastructure. Niche markets such as Pennsylvania Impressionism, Asian art, Americana and 20th century design were targeted.

“We persuaded Beau that less was more,” Nichol says. “A major turning point was a fine art sale in

2004 with a hammer total almost equal to that of the total annual turnover for Freeman’s in 1999 – but through selling 238 lots as opposed to 50,000.”

Freeman’s offering has since been refined to 30 annual auctions across 13 departments, with paintings and single-owner sales leading in revenue terms. Through increased specialisation, the annual volume has been whittled down to 8000 lots in the $500-plus bracket.

In a further step to secure the firm’s future, in 2016 Beau Freeman sold a controlling stake (the family retains a minority interest), together with the Chestnut Street building, to his directors. The move was just ahead of Beau’s death in 2017.

‘Get it right!’

Succeeding Beau as chairman in 2017 – the first non-Freeman family member to hold the post – Nichol is acutely aware of the legacy he and fellow directors have inherited. As he gazes up at paintings of his predecessors in the Chestnut Street boardroom, Nichol admits to feeling a certain weight on his shoulders. “You’ve got all these past members of the family looking down, and you feel them urging us, ‘get it right!”.

Expectations have never been higher than now, as Nichol and his fellow directors prepare to usher in Freeman’s next chapter: relocating from its offices of nearly 100 years to shiny new premises eight blocks away on 2400 Market Street, overlooking the Schuylkill River.

The new building will have the latest lighting technology installed across two salerooms with expansive white walls “to display paintings and objects properly”. It’s a far cry from Chestnut Street in the early days, Nichol recalls, having to use flashlights to view paintings and importing lighting rigs for auctions.

The larger saleroom will be for higher value lots while a second facility will serve as “the exchange for more moderately priced items, moved quickly through the system”. A programme of events is being developed “so we can play a bigger part in the cultural life of Philadelphia”.

Having sold Chestnut Street to a developer, the Market Street premises is leased, an arrangement that “concentrates the mind wonderfully,” Nichol says.

In a complex process managed by Dougher, Freeman’s 50 staff and 13 departments, including fine art, books, jewellery and 21st century design, have now begun to relocate, with the first auction at Market Street happening in late November.

For now, though, Nichol is meeting with ATG in the Samuel T Freeman Auction Co building, dating from 1924. With its revolving stage (a feature later copied by New York salerooms) it was the height of modernity back then.

Hi-tech new premises

But there isn’t too much time for nostalgia. Premises with a state-of-the-art gallery and saleroom above which sits 5000 square feet of space for staff offices, awaits. Nichol can concede that “yes, Chestnut Street is old and charming. However, in a globalised, tech-driven marketplace, it’s no longer fit for purpose or good enough for our staff to work in.” So antiquated is the building’s lift, it requires a dedicated staff member to operate it.

Does Nichol believe the ‘oldest auction house in America’ tagline is at odds with the firm’s high-tech drive? Freeman’s has been in or ahead of the game for some years – operating its own white-label bidding platform, Freeman’s Live, since 2017. It is about to put sales on the-saleroom.com to reach a wider audience beyond America’s shores, while the firm’s database marketing and website will be “completely overhauled” by next year.

Longevity and modernity can go hand-in-hand, Nichol replies, pointing out that the firm’s history acts as an important tool for winning business. “When you’ve been run by six generations of one family, and you’ve been in business more than 200 years, it reassures consignors and buyers that you’re not going to disappear overnight,” he says.

The seventh generation of Freemans remains involved in the firm and Nichol says prospective consignors are pleasantly surprised to meet Samuel T Freeman III, son of Beau and senior vice president of the firm’s Trusts & Estates department. “In an historic city, where venerable names resonate, Sam is a living embodiment of a tradition and that matters a great deal to people.”

Regional reach

At the same time, the firm extends its new business tentacles through regional representatives in Richmond, Virginia, Boston, Washington DC, Texas and Los Angeles. In New York, the firm’s rainmaker is local resident Nichol himself, from where he commutes two hours to Philadelphia.

Ask about other US regionals’ spread of offices around the US and Nichol shrugs. “In the age of the internet we’re not wedded to having real estate in every region. Location isn’t as important as it used to be; it’s far more vital to have talented people who can shake the trees and bring in business, catalogue accurately, be responsive to clients and be on top of marketing.”

He’s proud of the strong contingent of young people in the firm – “I walk around the office and I feel like the old guy” – and of newer hires, such as former dealer Darren Winston who heads Freeman’s Books, Maps and Manuscripts department. “Libraries are a good gateway to wider collections,” Nichol observes.

Art ambition

On the day ATG visited, Freeman’s staff seem excited about the move to Market Street, with its promise of well-lit and better presented auctions and exhibitions of work by local artists.

The new venue will also be a suitable canvas for Nichol’s aim to have “the best fine art department outside of New York” with fewer, but more high-quality lots. An exhibited artist himself, Nichol says Freeman’s has progressed “some way towards that”.

The firm’s most recent American art and Pennsylvania Impressionist sales, in December and June are a case in point, featuring 300 lots selling for a total of $6m including premium, Nichol says.

Summing up the firm’s business strategy, Nichol paraphrases Canadian ice hockey star Wayne Gretzy’s mantra of ‘skating to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been’.

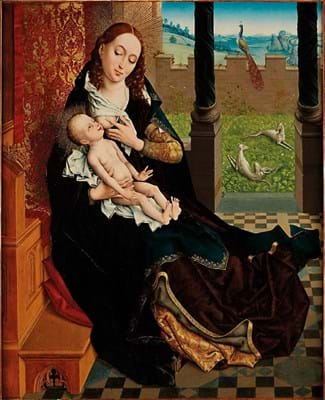

Nichol says: “Not many regionals do Old Masters, so you could say we go where the others aren’t.” A recent endorsement of that strategy came at Freeman’s February 2019 European Art and Old Masters sale of 40 lots for a premium-inclusive $3.2m, with one lot, a 15th century Flemish devotional painting, netting $2.05m (£1.58m).

When it comes to competing for single-owner collections, the firm asserts itself against Sotheby’s and Christie’s as well as other regionals with a focused, micro-sales approach underpinned by high-end catalogues.

In selling the collection of Campbell heiress and former Philadelphia resident Dorrance ‘Dodo’ Hamilton in April in 2018, lots were split into two sales: fine art, furniture, porcelain, silver in one, and jewellery in the other. Together they netted just over $6m hammer, with the main catalogue winning a design award for Freeman’s creative director, Whitney Bounty.

This boat race silver presentation punch bowl, made in the Japanese manner by Gorham bears a date mark for 1884. Inscribed to underside, 'Won By/The Sloop Hera/In a Match Race With/The Sloop Lillie/1883', the bowl is 9.5in high, 18in in diameter and weighs 119.1 troy oz. Part of the collection of Victor Niederhoffer sold by Freeman’s in June, the bowl sold for $85,000 (£67,150) against an estimate of $15,000-25,000.

“We’ve carved out single-owner sales that other auctioneers would have included in wider sales,” Nichol says. He points to the Brewster collection which Freeman’s sold in January 2018 for top estimate, whose 33 lots included works by Edward Seago and Eugene Boudin. “They would have been scattered into different sales by other auctioneers.”

As ATG takes its leave, we have one final look at the Freeman portraits, soon to be joined by one of Beau Freeman II “who’s very much in our minds as we make this move,” Nichol says.

Will there be a place for celebrating the Freeman history in Market Street? “Of course!” Nichol exclaims. “Tristram, our founder, and Beau will certainly come with us. We want that continuity. And after all, we’re not moving to the other side of the world. This is a Philadelphia auction house and always will be.”