An auction bristling with highly commercial, signed jewellery and objets d’art, the Bonhams (27.5/25/20/13.9% buyer’s premium) sale held on December 4 certainly hit the spot.

The market has become selective and picky and this offering catered to it.

The core was devoted to a European private collection of 23 desk clocks, the vast majority of which were made by Cartier between 1908-90.

In other words, the sheer range and variety of timepieces on offer afforded devotees of Cartier’s work a singular opportunity to study how the firm’s designs in a single medium evolved through the 20th century, from the elegance of Belle Epoque through Art Deco architecturalism to post-war functionality.

Unquestionably, the stand-out lot was one of the firm’s celebrated Pendules Mystérieuses produced in 1919 by Cartier and master horologist Maurice Couet (1885-1963).

Couet, who had remarkable insight where physics, mathematics and optics were concerned, worked in collaboration with Cartier in Paris from c.1911. In 1913 he produced the first mystery clock known as Model A. Bearing in mind that each clock took on average a year to create, the one sold at Bonhams was therefore one of the very earliest examples.

Its design is deceptively simple: a plain, rectangular block of rock crystal on a black agate base with white enamelled gold frame. The diamond-set hands appear to ‘float’ in space with no apparent connection to any mechanism or movement. This ingenious illusion is created by fixing each hand on to a rock crystal disc with tooth-edged borders, in turn driven by two axles concealed within the frame and by a movement hidden within the base.

This clock has a later pediment, but in spite of this, it soared above its £150,000-250,000 guide to fetch £490,000 (£603,062 including premium). With several other clocks fetching double or even three times their estimates, the collection achieved a highly satisfactory £930,400.

Outstanding provenance

Considerable interest was generated on the view by several early Cartier jewels but one stood out for its sheer size and outstanding provenance: an emerald, rock crystal, diamond and platinum necklace formerly owned by Vita Sackville West, the celebrated poet, author and garden designer.

It was reputed to have been a present from Vita’s mother, Lady Sackville, on her daughter’s engagement to Harold Nicolson in 1913 and was mounted with a large Indian emerald profusely carved on the surface with flowers.

From around 1911 Jacques Cartier travelled to India where he forged fruitful relationships with several important clients such as the Gaekwar of Baroda and the Nizam of Hyderabad.

This emerald, weighing almost 100cts, was undoubtedly one of the gems he purchased with a view to having it reset in a platinum and diamond frame perfectly suited to the prevailing taste before the First World War for exotic jewels redolent of the East. In 1994 Bonhams sold a not entirely dissimilar emerald jewel from the Sackville West collection for £210,000.

Twenty-five years later the necklace in this sale fetched a more modest £82,000 against an estimate of £50,000-70,000. The reason? The emerald had, very sadly, sustained several prominent and irreversible cracks. Condition, as ever, is paramount.

If ever there was one item destined to attract international interest it was the Cartier Art Deco aquamarine, diamond and platinum necklace. Composed of nearly 170cts of top-grade aquamarines and 9.6cats of diamonds, it was fashioned in a typical bold and vibrant geometric construction. Against an estimate of £100,000 – 150,000 it soared to fetch £370,000.

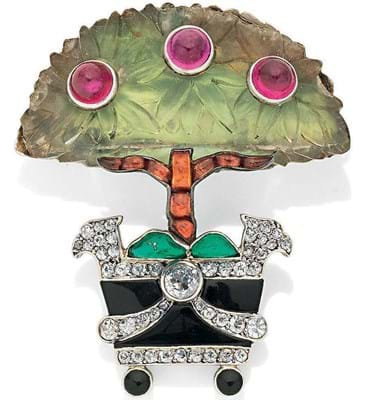

One of Cartier Paris’ earliest Orange Tree brooches c.1914 sold at £60,000. This is a rare example of the design and was created by Cartier Paris in 1914. The small brooch, standing just 3.3cm high, assumes a two-dimensional, highly stylised form, bursting with colour combinations and different shapes and cuts of gemstone: from the umbrella-shaped tree rendered in frosted rock crystal over a green foil, to the buff-top calibré-cut citrine trunk, and the use of shaped onyx for the pot with stylised bird-head handles.

The brooch displays all the characteristics of Cartier’s pioneering designer Charles Jacqueau (1885-1968), the man responsible for guiding Cartier away from the Garland Style, and has the maker’s mark of Henri Picq, Cartier’s main workshop supplier between 1900-18 (later the makers of many of the tutti frutti jewels). It had been a gift to Elizabeth Corbett on her wedding day in 1941 from Lady Jean Ward, granddaughter of US financier Darius Ogden Mills.

Independent designers

Leading jewellers at this time often did not always employ in-house designers and would typically use the same workshops to manufacture their jewels. Independent designers offered their models to different firms, sometimes selling identical designs to rival houses.

Very much in the Cartier idiom, but in a fitted case for fellow French atelier Lacloche Frères of 15 Rue de la Paix, Paris, and 2 New Bond Street, London, was an Art Deco diamond, onyx and enamel brooch c.1920.

Designed as a broche poigneé (drawer handle), it is pavé-set throughout with old brilliant and single-cut diamonds and cabochon onyx studs, in the style of the black and white ‘panther skin’ jewels made popular by Cartier during the 1920s. It sold for £38,000.

While the Cartier Art Deco style will always catch the eye, it was a pair of earrings by the French designer Pierre Sterlé which were to attract some of the strongest interest on the day. Sterlé (1905-78) was known for his use of diamonds in elegant fluid lines of organic inspiration. This pair, made in the early 1950s, suspended a pair of large, well-matched, detachable natural saltwater pearl drops.

Guided cautiously at £50,000-70,000, they went on to fetch over five times their lower estimate achieving £215,000. Fine gems, a wearable design and, above all, a highly desirable maker proved the perfect recipe for auction success.