“If we build a gallery, will you get us a dinosaur to fill it?”

There are precious few salerooms in the country that could accommodate a diplodocus or a Cold War-era missile. Fewer still that would know where to find them.

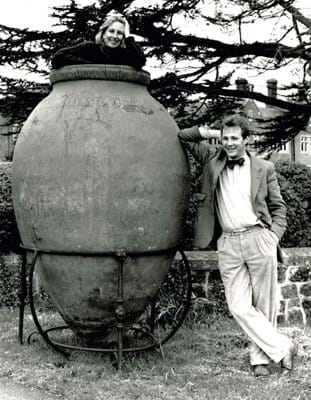

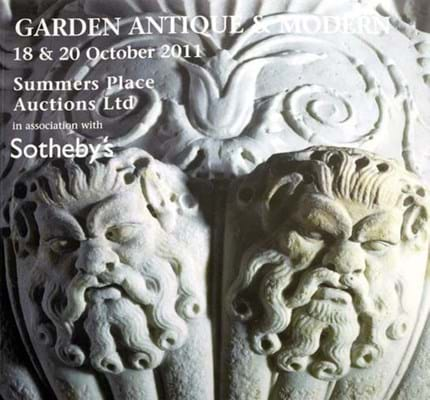

Summers Place Auctions is an operation like no other in the UK fine art scene. Biannual sales of garden statuary and architectural antiques have been held here, the site of a Victorian manor house near Billingshurst, Sussex, for three decades. And James Rylands has seen every one of them.

As he samples the Welsh rarebit at the nearby roadside cafe, he recalls the formative years when in 1979, as an art history graduate turned dustman, he attended an interview for a job at Sotheby’s.

Removing his earring for the occasion, Rylands greeted director Roger Chubb with his first impressions: “The staff have been extremely rude – and they didn’t know who you were.”

Somehow, adopting this high-risk strategy, he found himself being offered a job at Bearnes. The West Country firm was three years into a partnership with Sotheby’s and based at the Rainbow, a mansion overlooking Torbay.

Rylands had earned £80 a week on the bins. The equivalent wage as a Sotheby’s junior cataloguer was £40.

He first came to West Sussex in 1981, two years after a local business (the saleroom of Pulborough estate agent King & Chasemore) had been rebranded as Sotheby’s Sussex.

The move to Summers Place was made in 1985 – the perfect setting for the inaugural garden statuary sale conducted by the works of art department in 1986.

At the time Crowther operated a dealership at Syon Lodge with a similar raison d’être. Christie’s followed suit with ‘garden’ dispersals at Wrotham Park.

With an eye to cornering a burgeoning market in an era of regional expansion, Sotheby’s was persuaded by an ambitious £100,000 plan to remodel a six-acre plot and overgrown Victorian kitchen garden to create the verdant setting for two selling weekends a year.

Landscape architect Michael Balston’s scheme of meandering paths between ‘rooms’ walled by yew hedges has only now fully come to maturity.

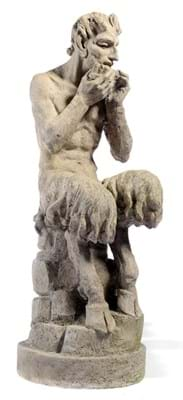

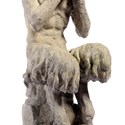

Even from the start it was all about private buyers – aimed squarely at those embarking on a project that might require a garniture of Coadestone urns, a pair of John Cheere figures, a Coalbrookdale bench or a set of suitably patinated terracotta rhubarb enforcers.

“The bean-counters were getting the upper hand and they don’t understand that in the auction business to get the jam you also have to sell the bread and butter

There were many more dealers active in the market in the 1990s and 2000s than there are today, but even then “if they managed to buy we looked on it as a failure”, says Rupert van der Werff. It was an early taste of the dish that would later be served across all Sotheby’s departments.

Van der Werff had joined Sotheby’s as a porter in 1997. His father had pulled a few strings to arrange an interview, cutting short his time as an archaeologist in Jordan and scuppering plans to work in Yellowstone National Park.

Within four years he was appointed head of the garden statuary department, running the operation with Jackie Rees as Rylands took a back seat to work on his TV persona while taking to the rostrum three times a week for Sotheby’s Colonnade sales.

Changing styles

Tastes were evolving. Urinating cherubs and cast iron began to disappear from the stands at the RHSChelsea Flower Show. Fossil decoration arrived in 1998 alongside the work of contemporary sculptors, for whom Summers Place became a cost-effective alternative to gallery sales.

Changes were observed at other levels. Garden statuary at Summers Place had survived the arrival of the entire Sotheby’s internet department and then the closure of the general saleroom in favour of the Olympia project in 2001.

But the company’s commitment to niche areas of the middle market it had championed in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s was waning. As Rylands puts it: “The bean-counters were getting the upper hand and they don’t understand that in the auction business to get the jam you also have to sell the bread and butter.”

Garden statuary in particular is a “market with associated costs”. Health and safety regulations are rather more relevant here than in most fine art departments. Van der Werff carries the scars of 20 years – he removed his eyebrows replacing a pressure valve on a forklift truck – but otherwise the record is good.

“We have lots of visitors and haven’t killed anyone yet. The only person who’s been badly damaged is me,” he says.

Seven acres, seven full-time members of staff, heavy plant and machinery are the sort of logistical challenges that would leave most hanging up the phone.

Who else would entertain the sale of 500 tonnes of statuary located in Massachusetts or a 15ft (4.57m) high bronze bust of Lenin, liberated from a town square in Latvia?

Currently, over 60% of clients are from overseas and a dedicated team dealing with transport and shipping is a necessity.

Unsold rates are also unusually high at around 40-50%. “Ten or 15 years ago we would have been upset by that, but lots of buyers are now out of the equation,” adds Van der Werff.

In this context, the decision to sell much of the material by sealed bids has been effective – “selling for the maximum rather than the minimum” is how Rylands puts it.

The format misses the open competition inherent in the public auction but it does throw up some extraordinary results for the kind of objects that “can be worth a lot of money to one individual”.

It is the type of experiment the firm has conducted in the 10 years since the opportunity to run its departments ‘in association with Sotheby’s’ arose in 2007. There was little hesitation, recalls Rylands: “When offered we said yes please.”

The association lasted until the apron strings were finally cut in 2012. The firm continues to do a lot of valuation work for Sotheby’s but there are no longer any formal ties.

A time for evolution

There is still something of the ‘old Sotheby’s’ about the place – from company secretary and departmental assistant Letty Stiles, who joined Sotheby’s in 1984, to Les Baker, who after 21 years retired as head porter in 2000 before being enticed back as the gardener. Department assistant Kate Diment joined Sotheby’s in 1995 and the garden statuary department in 2001.

Perhaps the most palpable difference has been in the fabric of the site – the old house long since converted to luxury flats – and the merchandise sold there.

The description of the current offering as ‘from Rome to chrome’ is as accurate as it is catchy.

In May 1998, not too long after the release of the Titanic movie, Sotheby’s garden statuary department offered a suite of Louis XVI style walnut and gilt panelling from sister ship Olympic. The 180ft (54.9m) of panelling, doors and windows, once part of the first-class restaurant, provided decoration to a modest flat in Southport. James Rylands met the owners and negotiated for the flat to be sold to a third party for around £40,000 on the understanding that the panelling would come to auction. Although unsold during the sale, the auctioneers later received a call from a cruise ship company who subsequently bought it for £120,000.

Rylands and Van der Werff’s plans for Summers Place started modestly with the upgrading of paths and the restoration of the stone summer house in the arboretum. Adjacent is the contemporary sculpture garden framed by yew and hornbeam hedges.

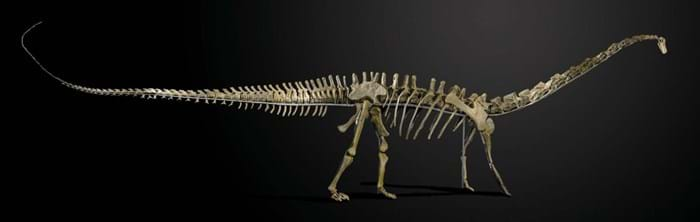

But it was with the construction of a vast new interior space, a gallery with a glazed atrium and walls panelled with a slate veneer, that the duo demonstrated their ambitions beyond the herbaceous border.

The Morris Weller Gallery, named after two former managing directors at Sotheby’s Sussex, Alistair Morris and Leslie Weller, was formally opened in October 2012, shortly after natural history specialist Errol Fuller was asked if he could lay his hands on a prehistoric giant to properly test the dimensions of the new structure.

Fuller duly obliged and found a 150 million-year-old, 57ft (17.4m) long diplodocus skeleton that generated untold column inches of positive publicity for the saleroom and later sold for £400,000 to the Danish Natural History Museum as part of the firm’s inaugural Evolution sale.

Rylands and Van der Werff continue to “search for niches”.

Evolution added four further sales a year to the SPA calendar, followed in March with a sale titled Conversation Pieces – a mix of natural history, garden antiques, antiquities and boys’ toys led by a customised 1960s Bedford ice cream van customised by Dinos Chapman which sold for £21,600. The verdant gardens of Sussex are now the place to go for a gold-plated rocket engine or a Spitting Image puppet.

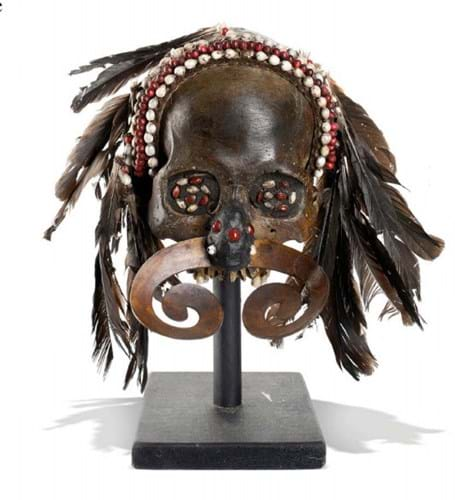

Coming up in June is SPA’s first auction titled Tribal Art & Travel – “an area worth experimenting with”, says Van der Werff.

A Dayak ancestor skull decorated with feathers, seeds and nose piece, estimate £2000-3000 on June 13-14.

A collection of 56 lots collected in the Sepik river area of Papua New Guinea during the middle of the 20th century (most lots pitched at under £500) is supplemented by objects as diverse as a Dayak ancestor skull (estimate £2000-3000) to a pair of beaded and buckskin moccasins c.1870 from the Sioux of South Dakota (estimate £1000-1500).

Van der Werff concedes that not everything the firm has tried has or will be successful.

But “just like back in the ’80s, we want to be market makers rather than market reactors”.

Summers Place – a brief history

■ 1979 Sotheby’s purchases business from Pulborough estate agents King & Chasemore

■ 1985 Sotheby’s Sussex moves to Summers Place

■ 1986 First garden statuary sale at Sotheby’s Sussex

■ 1987 Walled garden designed by Michael Balston

■ 2001 Sotheby’s Sussex closes. Garden statuary sales continue at the venue.

■ 2007 Summers Place Auctions established

■ 2012 New gallery was formally opened

■ 2013 Inaugural Evolution sale