However, increasingly, maps which an earlier generation of dealers would have labelled simply ‘curiosities’ or ‘novelties’ have entered the collecting mainstream. The canon of printed maps and plans which appear in major auction houses and dealers’ catalogues has now expanded to include material from every era, from the 15th to the 21st century.

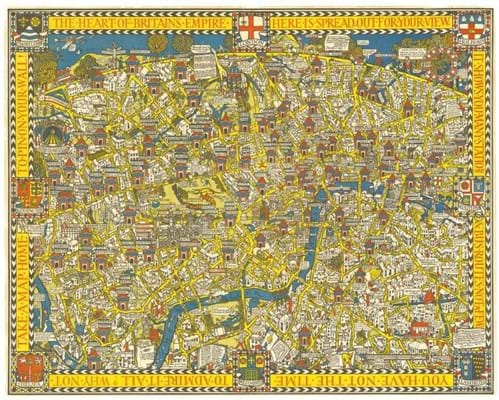

The rising stars are often the later 19th and 20th century issues: the products of wartime propaganda, early London Underground maps or the whimsies of MacDonald Gill. Many have graphics and sentiments that chime with ‘modern’ tastes and some, previously dismissed as the product of mass production, have proved to be genuinely rare, both in commerce and institutional collections.

Harry Beck’s ‘Tube’ map was first displayed on station walls in March 1933; only a handful of posters are known to survive, and one is likely to set you back over £30,000 – if you can find it.

It means that modern collectable maps are no longer the quirky budget option they once were. In recent years the market has morphed to a point where the prices of popular 20th century issues equal or exceed some of the traditional mainstays of the trade.

Centuries apart

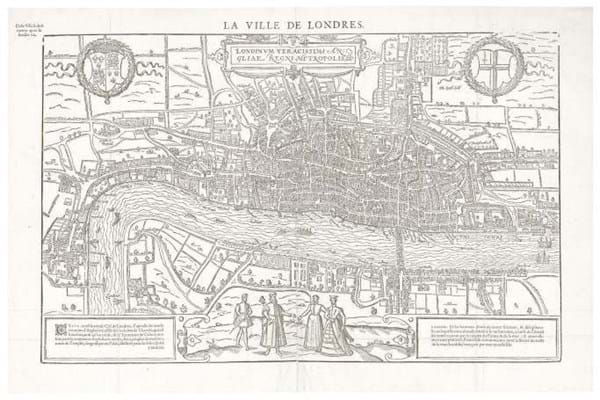

Earlier ‘historical’ maps can appear undervalued in comparison. Consider, as a single example, two well-known maps made roughly three and a half centuries apart: MacDonald Gill’s 1914 ‘Wonderground’ map of London, which inspired a generation of comic pictorial maps, and Francois de Belle Forest’s fine 1575 woodcut plan of London, which is only the second surviving printed map of the city. Both are currently offered by Daniel Crouch Rare Books for £3000 each.

However, this is not just a case of new replacing old in the collecting arena. The market has become more sophisticated. Factors other than age, size, decorative appeal, quality of printing or even quality of cartography are now in play. And it is the study of modern maps that is informing how we treat their predecessors.

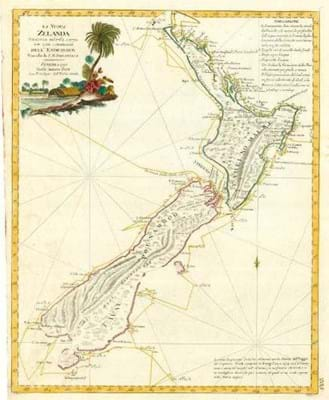

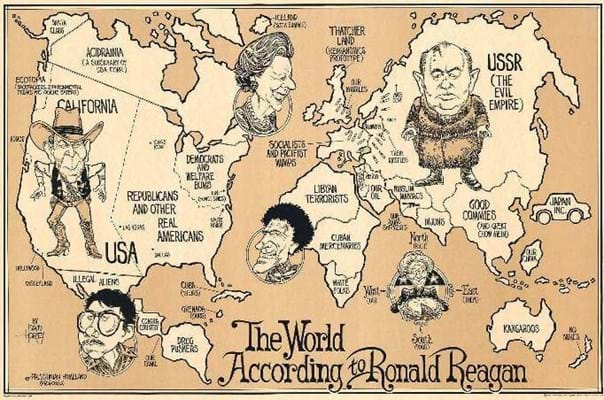

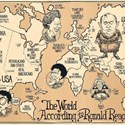

The Altea Gallery currently has in stock David Horsey’s 1987 The World According to Ronald Reagan priced at £1600 (incidentally the same sum as a 1778 printing of Captain Cook’s map of New Zealand published in Venice by Antonio Zatta).

This West Coaster’s view of global politics in the age of the superpowers perfectly encapsulates Cold War certainties: ‘our missiles’ and ‘their missiles’; Reagan and Gorbachev facing off like gunslingers in a spaghetti western with ‘Thatcher Land’ in between (depicted as the same size as the whole of continental Europe, a collection of ‘socialists and pacifist wimps’).

Modern collectable maps are no longer the quirky budget option they once were

Less visceral, perhaps, than Gillray’s 1793 ‘New map of England & France’ which famously shows George III as John Bull, defecating violently in the face of France and scattering a French invasion fleet (Jonathan Potter currently has the 1851 reissue for £750). However, the political undercurrents are hardly less subtle. It is a prime example of what is known today as ‘persuasive cartography’.

Persuasive cartography is not a new concept. It has long been understood that the artistic elements on early printed maps are not there by accident. They were expensive, luxury items, and their owners wanted to be seen as patrons of the arts as well as the sciences. There was political point scoring too. Look again at that ‘Golden Age’ map from Amsterdam showing Flemish ships in the Medway or off the coast of Sri Lanka. It is making a point: we can map you, we can reach you.

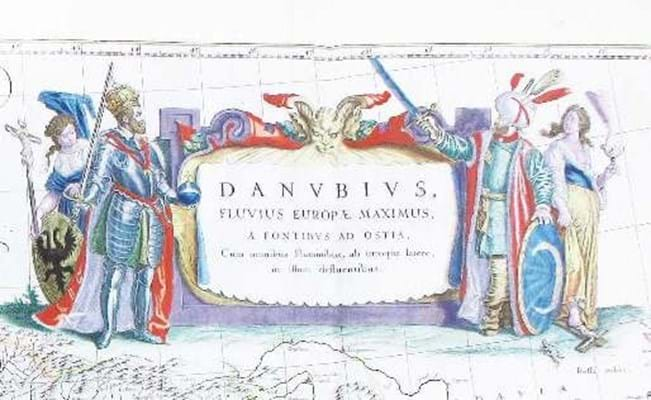

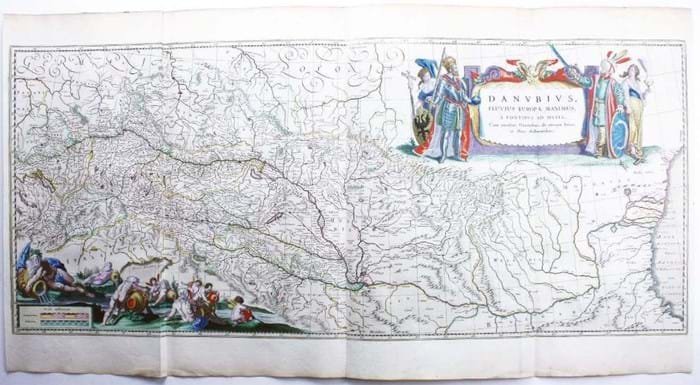

One of the largest and most decorative atlas maps from this period is Blaeu’s map of the Danube from source to mouth (a copy with original colour is available from Mary Louise Bryan at £1500).

The Danube was one of the great commercial arteries of Europe, and a natural choice for a map like this, but it was also the 17th century divide between the Ottoman world and western Europe. Collectors today are as likely to marvel at the cartouche depicting two figures with drawn swords (the Austrian emperor Ferdinand II facing a more generic Turkish sultan) as they are at the allegorical figures representing the mighty river and its tributaries. Like Horsey’s view of Reaganomics, this is a map with a message.

It is increasingly provenance and marks of ownership which set an item apart

Stalwarts today

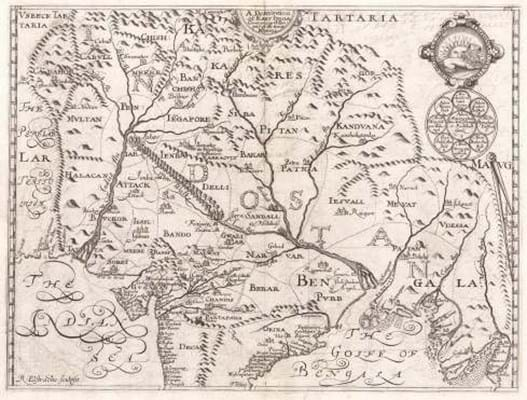

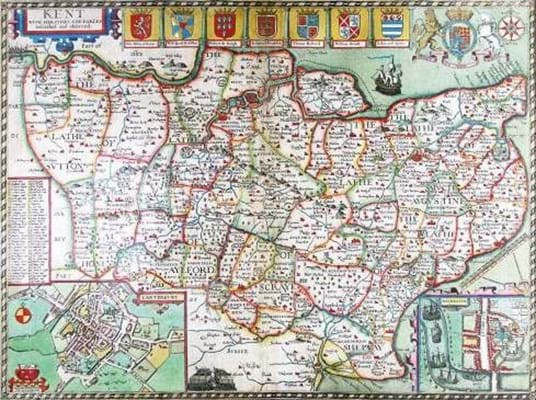

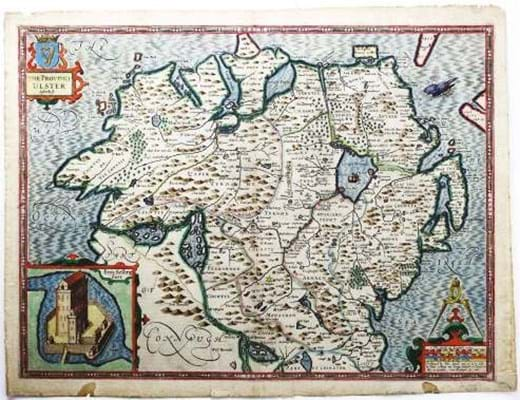

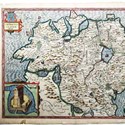

The same ‘modern’ criteria are being applied to stalwarts of the trade. John Speed’s county maps – traditional decoration on the walls of homes, offices and country pubs – have long been admired for their observations on the relative size and importance of towns and cities or the principal routes of trade and movement 400 years ago. But it is also possible to look at Speed with a quite different eye.

His inclusions and omissions raise intriguing questions. For example, when preparing his map of Ulster (Bryars & Bryars, £950) Speed seems to have had little or no access to the best official maps (including those by Richard Bartlett who was beheaded by the locals of Tyrconnell ‘because they would not have their country discovered’) and made no effort to update his map after 1610 to reflect the growth of new plantation towns. Both are a good indication that few of Speed’s early readers used his maps as navigation aids. Instead, with decorative coats of arms and battle scenes conforming to his own Stuart-friendly version of British history, Speed’s maps are about power and persuasion as much as any wartime propaganda map.

As well as the stories behind the mapmakers, we now want to know more about the owners and users of maps. In common with every other part of the antiquarian book trade, the internet has made it easier than previously possible to compare examples and gauge how frequently they appear on the market. So stories are important. It is increasingly provenance and marks of ownership (as well as the traditional variable of condition) which set an item apart.

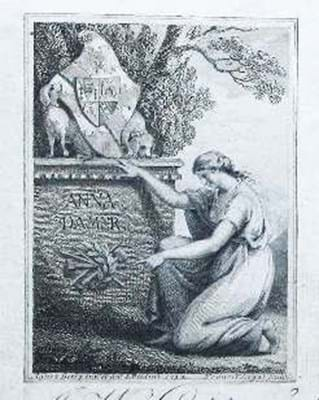

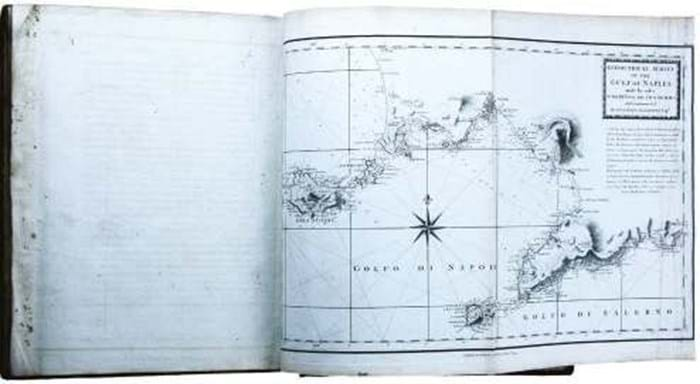

Bryars & Bryars currently has an example of William Faden’s Le Petit Neptune Français; or, French Coasting Pilot, a quarto atlas of the coastlines of France and Italy as far south as Naples published in 1793 soon after the outbreak of war with Revolutionary France.

There are others on the market, but this one carries the bookplate for Anne Damer, the sculptor to whom Horace Walpole would bequeath Strawberry Hill. In 1798 she had visited her friends Sir William and Emma Hamilton in Naples where she had met Nelson, who sat for her and gave her a coat worn at the Battle of the Nile. It is probable that the book, which later passed to a family of silk dyers in Coventry, had accompanied Damer on her continental travels.

Through easier access to such knowledge our understanding of maps and the lives of their makers, publishers, engravers and readers is being constantly enhanced. As collectors begin to move easily between five centuries of cartography, has there ever been a richer or more stimulating time to engage with the world of old maps?

Tim Bryars is a director of Bryars & Bryars and co-organiser of the London Map Fair held at the Royal Geographical Society from June 8-9.